Closer to the end - South Colombia till Medellin

Closer to the end - South Colombia till Medellin

At the border between Ecuador and Colombia, in Puente Internacional de Rumichaca, I spent most of my time trying to find a parking space on the Ecuadorian side.

Migraciones had a short line and Adounas had none at all. I continued on to Colombia, passing vendors selling SOAT and SIM cards and an uninterested customs officer.

On the Colombian side, another customs officer told me to park right next to Adouanes and behind the barrier. No sooner said than done, I went to Migraciones and picked up the stamp. Then I looked for the shop Hans had recommended among the stalls. It was the second one, and Richard filled out the form for USD 25 in 15 minutes. I realized my mistake relatively quickly, but hindsight is always easy.

I received a confirmation email from

Equipped with COP and a SIM card, I went to Olga Mejia at Multiseguros OMC. Although I had sent her everything by email beforehand and actually only wanted to pay in cash, I spent the next hour watching the ladies prepare my 30-day SOAT for Colombia. It cost 120'000 COP.

I had picked up a few chorizos at Plaza 20 de Julio beforehand, otherwise I would have been hungry. If you need something, you can find it in Ipiales. From supermarkets and banks to shoe stores, everything is available here.

Since I hadn't found a suitable place to park around Ipiales and it was already almost 4:00 p.m., I had to skip the Santuario de Nuestra Señora del Rosario de Las Lajas because I wanted to spend the night in Pasto.

I drove to Pasto in two hours on a perfect highway in light rain.

The evening didn't get any better, and it was supposed to rain for several hours the next day. The main difference was that it was over 30 degrees in Pasto and halfway to Popayán, the drive turned into a journey through the rainforest.

My drive from Pasto to Popayán took over 6 hours and apart from lots of forest, mountains, rugged valleys, and a few villages, I didn't see much. The beautiful highway had turned into a simple but good road.

On the way, I treated the Dog.O.Mobil to its second exterior wash. Four Colombians removed the mud from the PN Angel and polished the van to a high shine for only 40'000 COP.

Pasto was a simple, functional city, not really beautiful. Popayán, along the Pan-American Highway, looked similar. I didn't go into the old town itself.

When I arrived at Finca La Bonanza “Chez KIKA” that evening, I was exhausted. It was the first time I had met overlanders again whom I had previously met in Cuzco or at Finca Sommerwind.

Kika and Anouar run the campsite and, on the side, the best Moroccan restaurant in South America.

I had actually planned to make a detour to a rum distillery in Silvia on the second day. But my visit to the Tienda artesanal indígena Tsatsø ya didn't happen because the ELN had called for attacks on police stations and Kika advised everyone to stay at the campsite.

I didn't know the ELN, only the FARC, but I took her advice seriously and used the day to clean the mud off the inside of my Sprinter and prepare for the Moroccan dinner.

On the internet, I found that the armed conflict in Colombia is one of the longest armed conflicts in the world. It officially began in 1964 with the founding of the FARC and the ELN. Then, in November 2016, after some difficulties, a final agreement was reached to end the conflict. The status today is that the conflict is still active, and I read news such as

“The Colombian government and the rebel group known as FARC signed a three-month ceasefire on Monday and officially began peace talks. President Gustavo Petro is attempting to support his plans to pacify rural areas ahead of the regional elections taking place at the end of October.”

Or

“The Colombian government signed a six-month ceasefire with the National Liberation Army, the country's largest remaining guerrilla group, in June. But talks with the Gulf Clan, the country's second-largest armed group, collapsed earlier this year when the military cracked down on illegal mining in a region controlled by that organization.”

I hadn't noticed anything about it until now, and I wouldn't notice anything about it in the coming weeks either.

After nine months, I also realized that I had to be in Cartagena in about three weeks. Google estimated the direct route to be only about 1'300 km, but with a travel time of 22 hours. If I wanted to visit Cali, Bogota, and Medellín, it would be 1'700 km and 32 hours of travel time.

I had to come up with a compromise, because I definitely wanted to spend a few days in Cali, Medellín, and on a Caribbean beach. I also wanted to go on a coffee tour and, if possible, a cocoa tour.

For my cocoa tour, I had Cinco Cacao in mind. For coffee, I had chosen Finca Café Tío Conejo or Café Historias Tour Cafetero.

After a stop in Silvia, I actually wanted to buy a Ron Artesanal, but ended up buying a Whiskey Artesanal instead. At 10:00 in the morning, I was able to taste 3 options at the Tienda artesanal indígena Tsatsø ya. Thanks to Kika, because the Tenienta produces really delicious rum and whiskey. Afterwards, I headed to Cali.

The temperature around noon was about 32 degrees Celsius, and everything went well until Peaje Villa Rica. From there, it took over two hours to get to my parking spot at the Hotel Villa Bosco via Cali. There was a complete roadblock and a tremendous amount of traffic in Cali. Cali differs from many South American cities in its suburbs. It is modern, clean, and in good condition.

And on Sunday, we headed into Cali. Until now, I had never found it so difficult to form an opinion.

Here are a few facts. Cali is the capital of the Colombian department of Valle del Cauca and the third largest city in Colombia in terms of population (approx. 2.5 million in the city and approx. 3.2 million in the region). Cali was founded in 1536, making it one of the oldest cities in America. Cali is located at an altitude of approx. 1,000 meters above sea level at the confluence of the Río Cali and Río Cauca rivers. It was hot and humid on the day I visited, with temperatures around 32 degrees Celsius.

Cali used to be a dangerous city, but it no longer ranks among the 20 most dangerous cities in the world.

Perhaps I should mention something positive, for example, that Cali is the birthplace of salsa.

I had put together my tour on Komoot and it started with a walk along the Río Cali and a visit to the cat park. At 32 degrees, I spared myself a visit to Cerro de Las Tres Cruces. Through Barrio San Antonio, I made my way up to Parque San Antonio. In addition to the good view, you also have good cell phone reception up here, as there are so many antennas and power generators. Took me a minute to find a view that does not show the antennas

In Barrio Navarro-La Chanca, I took a look at where the locals live. And I wondered whether I should go to Plaza de Cayzedo or check out Galería Alameda for local specialties. I wanted

- Cholado is a fruit ice cream sundae

- Lulada - A drink made from lulo, also known as quitotomate, lime juice, water/condensed milk, and sugar for sweetening

- Arepa - Arepa is a type of kebab made from corn dough with meat, salad, and sauces.

I finally headed towards Plaza de Cayzedo. The first thing that caught my eye were the poor people sitting or sleeping on the side of the road. The closer I got to the Iglesia Santa Rosa de Lima, the more littered it became.

It was a new experience for me when a black man on Carrera 10 smashed two bottles and rushed towards another black man, who was holding a damn long knife in his hand, shouting. The traffic continued unperturbed and the two policemen, who were standing less than 40 meters away, didn't care that the two were about to stab each other. It seemed to interest only a few onlookers like me, no one else.

I continued on to Plaza de Cayzedo. The plazas were a highlight in most cities, but not in Cali, at least for me! I noticed the older prostitutes looking for clients. In the immediate vicinity, I also saw the hourly hotels. The Centro was rather dingy, and the few junkies loitering around didn't make it any better. By now it was noon and I wanted something to eat. In the Centro, I could buy fried chicken, papas rellenas, and empanadas. It wasn't really possible to sit down comfortably.

I was drawn to Barrio Granada with its restaurants. On the way there, I tried to buy a lens cap at the Centro Comercial Centenario. But in Cali, many shops were closed on Sundays. I only mention this because at around 12:30 p.m. on Sunday, a Catholic mass was held in the foyer of the mall.

At Cantina La 15 Granada, I treated myself to a few tacos and a beer for a lot of money. I would call Granada a rather upscale neighborhood, but even here I saw a poor man sleeping in the gutter next to Starbucks.

Was I just in the wrong place at the wrong time, or was Cali's Centro a new experience for me in South America? In any case, I couldn't bring myself to go to Galería Alameda afterwards.

For the following week, I had planned to take a cacao and coffee tour in the Eje Cafetero.

Colombia's so-called coffee axis. Four hours' drive north of Cali lies Armenia and the Departamento Quindío. This is where I found what I was looking for. I should say that there are endless options.

The first stop was Armenia, the capital of the Departamento Quindío. The city is nestled in a beautiful landscape and, with a population of around 320,000, can be described as functional. Perfect for shopping, but otherwise rather boring. The last 7 km to Finca Evelyza were a bit bumpy and the only dirt road on the almost 300 km.

The Cacao Tour (80,000 COP in EN) was great. Three hours of information and cacao experiences. David and Karol really made an effort to get their visitors excited about cacao. The finca has been around for 15 years and is only 1.5 hectares in size, but the two of them do a lot to make the tour as varied as possible.

In addition to cacao, there are bananas, avocados, and other fruits to see. Hummingbirds flew around us as we turned the beans into edible chocolate. The parking lot was crooked, but I stayed there overnight.

I stopped for coffee 20 minutes north of Armenia. South of Salento is the El Recuerdo coffee farm. While the Evelyza finca was family-run and just getting started, the El Recuerdo farm was a functioning tourist business in an area where every other farm offers a coffee tour.

That's not bad, but it's simply a contrast. My tour in EN was informative, and I noticed that my guide had studied. I got a great introduction to the operation of a 4.5-hectare farm and how it differs from agricultural businesses. Less emotion and more facts were offered here for 45,000 COP. For 25,000 COP, I could stay here and drink more coffee.

I learned that the “good, flawless beans” were sold abroad and that Colombians drank coffee made from defective beans. In addition, the coffee was made as filter coffee and espresso machines are not often seen.

And while I was chilling out in the afternoon, the owner came by and we talked about Colombian specialties. I added the following to my list

- Cranisado de cafe: Colombian iced coffee

- Bandeja paisa - a traditional bandeja paisa consists of red beans with pork, white rice, minced meat, chicharrón, fried egg, plantain (plátano maduro), chorizo, arepa, hogao sauce, blood sausage (morcilla), avocado, and lemon

- Limonada de Coco -

INGREDIENTS

Coconut cream: This makes the drink thick and creamy.

Crushed ice: To make the lemonade cold.

Limes, sugar.

Put all the ingredients in a blender until smooth.

I made the Limonada de Coco myself and it was drinkable on my second attempt.

Via Salento and Pereira, I traveled along the Rio Cuca to La Pintada. Salento is a small, beautiful village surrounded by coffee plantations. At 9:00 in the morning, I encountered hikers, horse riders, and buses on the dirt road before I even reached the village.

To the east lies the Cocora Valley and the Parque Nacional Natural Los Nevados. I had toyed with the idea of going on a hike in the park, but I only had two weeks left before I had to get the motorhome ready.

It wasn't easy to park the motorhome along the very narrow streets because there was also construction work going on.

But during my short walk along Calle Real, the shops glowed colorfully in the morning sun.

I was overwhelmed by the crowds of tourists looking for tours or setting off on their own. It was impossible to take a picture without people in it. On the way to the Pan-American Highway, I encountered more crowds of tourists.

On the way to Pereira, I left the rainforest and drove into a valley basin filled with about 730,000 inhabitants. I bought bread and cake at the side of the road and drank my first Cranisado de Cafe. Colombians like it sweet, I would say.

This city was also a huge shopping center along the Pan-American Highway. It was impossible to drive through comfortably because cars, trucks, and motorcycles were coming from all directions at all times. The closer I got to the center, the less I felt like seeing the city.

In La Pintada, it was 32 degrees Celsius, with trucks as far as the eye could see and police checks. I found a parking spot at a swimming pool, between the town thoroughfare and the Pan-American Highway. At least I could cool off in the pool in the evening. My bandeja paisa in the late afternoon was quite OK; I would call it the South American version of a butcher's platter.

I tried to buy some decent bread or rolls here too, but most of the time there's only pandebono, a kind of sweet bread with cheese in the dough. Officially, it's bread made from corn flour, cheese, cassava starch, eggs, and a dollop of guava jam. There are many variations on pandebono ---> https://www.tasteatlas.com/best-rated-breads-in-colombia

You can also get something sweeter by buying a ROSCÓN DE BOCADILLO. And if you want something even sweeter, try aborrajados or a variation thereof, like I did. Aborrajado is made from sweet plantain slices filled with cheese, breaded, and deep-fried. Mine were baked, coated with a kind of buttercream, and sprinkled with coconut flakes or nut crumbs. I always like to eat two sweet treats in the afternoon, but after one aborrajado, I didn't need a second one.

That night was the first night I missed having air conditioning. With the windows open, the noise from the street was unavoidable. With the windows closed, I was baking in the motorhome at 27 degrees in the evening. Sleep-deprived and with a headache, I set off along Ruta 25 to Medellín.

It was only 96 km to the parking spot in the mountains above Medellín, but it took four hours to drive on a well-paved road. Heavy goods vehicles struggled to climb 10 to 20 km from 500 m above sea level to 2,500 m, and on the winding, steep road, it was impossible to overtake, at least for a German with a Sprinter who wasn't completely crazy.

Medellín itself was fine at first, like a big city in Europe. Well-kept houses and shops.

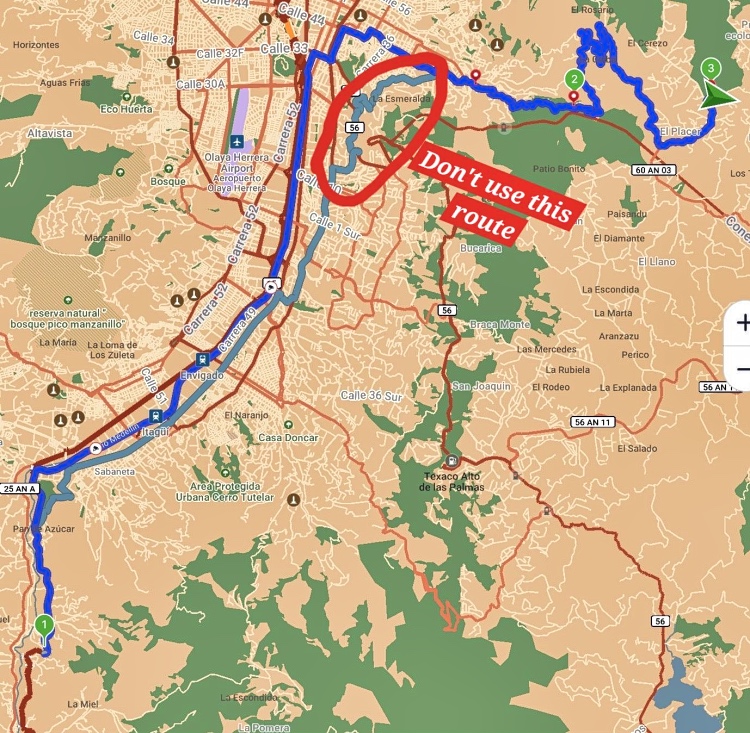

Maps.Me wanted to do me a favor and save me 400 meters of the difficult route. To do so, the app sent me into a barrio with steep slopes and narrow streets. The crowning glory was a route through a barracks. The guards at the entrance laughed when they understood where I wanted to go and that I couldn't take the shortcut through the barracks. I had to back up 200 meters and turn onto a busy road. But I managed that too.

Medellín is the capital of the department of Antioquia. With more than 2.6 million inhabitants, Medellín is the second largest city in Colombia, but including the suburbs, it has over 4.2 million. When you turn off the Autopista Sur or the Aburrá Valley, you immediately notice the difference in altitude between the city center (1,500 meters above sea level) and the Al Bosque campsite (2,600 meters above sea level). Steep roads lead up into the hills, and if you want to leave the city to the east or west, you have to drive over the mountains, which means climbing and descending 1,000 meters.

The next day, I took the bus from Al Bosque Camping into the city. As is customary in South America, the bus stops where people are standing and not just at bus stops. Just raise your hand when the bus comes. That's why there is no timetable. You stand, hopefully in the right place, and wait.

The journey cost just over 4,000 COP and took almost 45 minutes. You pay the bus driver and don't need a card. Afterwards, my knees and spinal discs ached, because the journey in the small bus was not suitable for people with heavy loads or disabilities.

Then we walked to the Centro. Between Plaza Botero, Plaza Cisneros, Av Oriental, and the Rio Medellín, there is a huge indoor and outdoor shopping area. Pretty much everything is sold here. From sneakers, caps, clothing, and food near the Metro Line A to everyday items in the western part of the area. After an hour in an endless crowd, I realized that almost all the stalls were selling the same shoes, caps, and items. In some cases, the same stalls with the same items were located 30 meters apart. I couldn't find a single stall or store selling cameras or lens caps in the entire Centro.

If you want to see the whole thing with a guide, you can book a free tour in English. I “joined” a tour for a few meters, but then went my own way. While I was there, I got a free tour of Comuna 13 in English from GuruWalk.

At Plaza Botero, I saw 23 sculptures by the artist Fernando Botero, surrounded by vendors, prostitutes, and a few drug dealers. I didn't really notice the police. I had seen junkies more in Plazoleta de Barrio Triste and on my way to the Jardín Botánico.

Around Plaza Botero, there were museums, the Palacio de la Cultura Rafael Uribe Uribe, and, of course, hotels, simple restaurants, and malls.

I walked north along Bolivar, first finding stalls and tiendas selling food. The further I walked, the more run-down it became, and I found a new variation of rummage tables.

I had expected a variety of street food, but I was disappointed. It was almost always the same. Fried chicken, papas rellenas, fries, rice, and beans. Occasionally a pizza or Chinese food.

The only thing I hadn't tried yet were patacones. Green plantains are cut into thin slices and shaped into a kind of potato pancake, then deep-fried. Three pieces cost 2,000 COP, served with salsa, of course (which was the best part). The texture was greasy and chewy, with a crispy edge. One napkin wasn't enough to clean my hands afterwards.

Writing this down, I realize that it might give the impression that my Spanish is good. Far from it. I can order and pay, but afterwards I spend a long time Googling until I find the right name. And as with the patacones, my hands got so greasy so quickly that I couldn't take any pictures with my cell phone. When I was traveling alone in most cities, I only used my cell phone. I only had my camera with me when I was traveling with a group or knew the place and it wasn't crowded. That was purely a precautionary measure, and nothing was stolen from me in South America except my license plate.

Anyone who needed spare parts for their motorcycle or had to have their motorcycle repaired could find options along Calle 57 to 59. I thought the whole area was OK, but I was later told that it was not an area for foreigners.

I only looked at the Jardín Botánico from the metro because I was interested in seeing more of the city than just the Centro.

The metro is clean and ultra-modern. You buy a card (from a machine or ticket office), load it with COP, and off you go. For a little over 3,000 COP, you can pass through the barrier and ride until you leave the metro at any station. The metro map is quite clear. While searching for a bus map, I found a map of the whole of Colombia, or rather the one provided by the government.

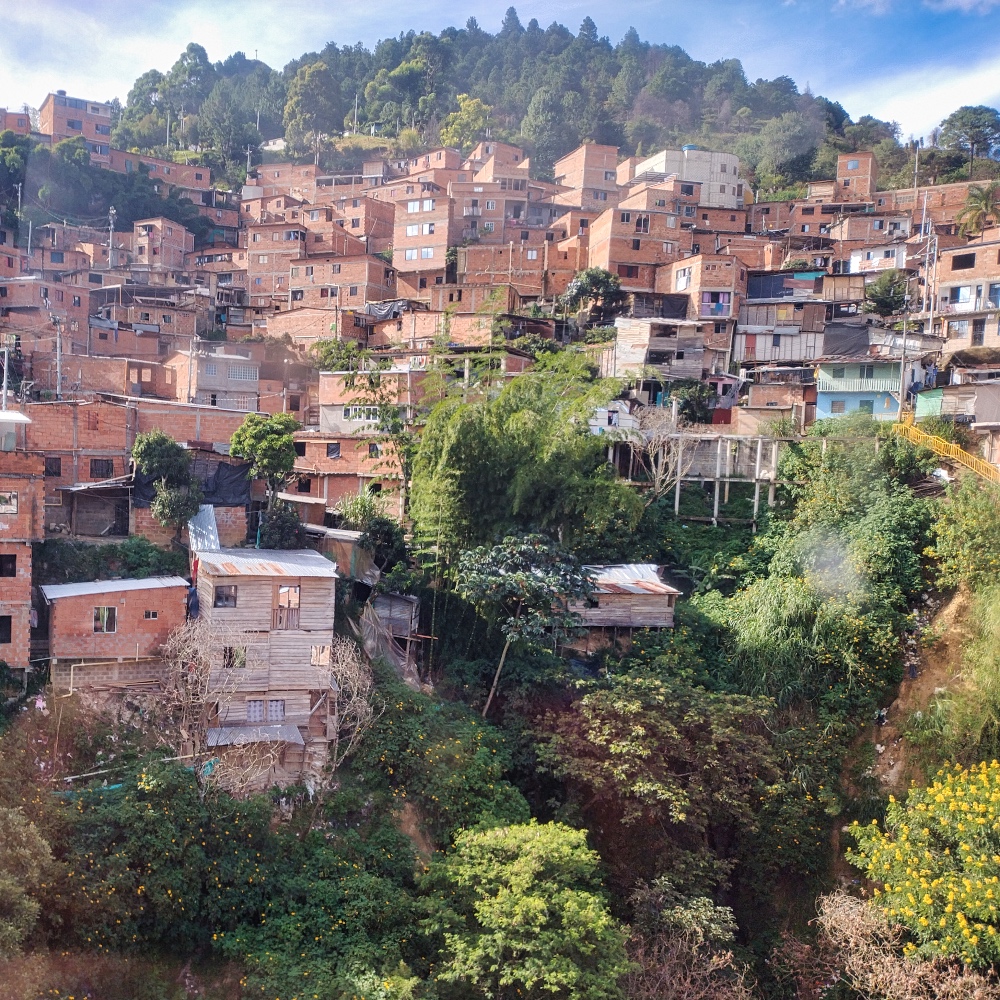

The Centro didn't look much better from above in the metro. I changed lines and took the green line T to Oriente. The further I got from the Centro, the more tranquil Medellín became. In Oriente, I boarded the MetroCable H to Sierra. Looking at a barrio on the steep slopes from above is quite different from wandering through the hustle and bustle.

You have a different perspective. But in Sierra, I couldn't get a taxi to take me back to the campsite. So I went back down and realized that it was only 50 meters from the Oriente station to Via Santa Elena. I stood at the side of the road, stuck out my hand when the bus came by, and rode back up to the campsite.

I then visited Santa Elena with Sacha, my neighbor at the campsite. From there, you have a good view of La Piedra del Peñol in the east and Medellín in the west.

Medellín's most important festival will take place in 2025 between August 1 and 10. For 10 days, flowers take center stage, and many of the arrangements are made in Santa Elena, the city of flowers.

Even during the hike, you could see flowers and arrangements in the village. There was a market in the village square, and an elderly woman “apparently” explained how to make the arrangements and told us something about the history. I didn't understand much.

I had considered continuing on to Cartagena via La Piedra del Peñol, Medellín's Sugarloaf Mountain. La Piedra del Peñol is a massive rock with a panoramic view that can be reached via a staircase with more than 600 steps. But the route to the Pan-American Highway after that seemed to be a rough track. Besides, the rock is located next to a reservoir and is a tourist attraction, so not really my thing.

The second day trip to Medellín took me to Comuna 13. I had found a local guide through GuruWalk, Juan Giraldo, who lived in Comuna 13 until three years ago. He gave the small group a really good insight into the history and background.

Here's what I remember. Made famous by the escalators that were built between 2010 and 2013, it is now a tourist magnet. However, the relevant history of Comuna began with the influx of people from the countryside who were driven from their farms by the FARC and ELN in the 1970s and 1980s. The neighborhood was controlled by cartels and the FARC/ELN guerrillas from the 1980s until the 2000s. During those years, up to 15 people died every day in Comuna 13.

In 2002, the government carried out 11 military interventions in the neighborhood with the aim of expelling/destroying the guerrillas. In 2002 alone, there were 450 illegal arrests of residents, 75 deaths outside of combat operations, nearly 100 disappearances, and more than 2,000 missing residents, whose whereabouts remain unknown to this day. A mass grave was found, but the investigation is progressing slowly.

And so I came to Comuna 13: Take the Metro B to San Javier and then take the bus or walk (approx. 30 min) to Comuna 13. And this is how it looks like if you arrive on a normal afternoon at Comuna 13.

From here, we went up the hill. The Comuna is a barrio nestled on the slopes of a valley. Narrow paths where tourists and motorcyclists make their way. Walls with beautiful murals and occasional graffiti. A mural is a wall painting with a lot of hidden information, without text. The famous murals are repainted every few years, and participating in this is not so easy. Juan made an effort to explain the meaning of the murals to us, as well as the importance of the animals in the pictures.

There were also restaurants, galleries, cafés, shops, viewing platforms, and tons of tourists along the escalators.

The tour, including a coffee tasting and several stops at shops, lasted almost three hours. I had started the tour with a MetroCable tour and a view of Parque Arví and took the bus back to Santa Elena. Unfortunately, I didn't know that not every bus passed the campsite, so I ended up discovering the villages south of Santa Elena.

The Stage

More Pictures

Videos

Latest Posts

-

Closer to the end - South Colombia till Medellin

Closer to the end - South Colombia till Medellin -

Ecuador - La Balsa to Tulcan

Ecuador - La Balsa to Tulcan -

Lima to Ecuador

Lima to Ecuador -

Lima from beginning to end

Lima from beginning to end -

Cuzco to Lima

Cuzco to Lima -

From Lake Titicaca to Cuzco

From Lake Titicaca to Cuzco -

Bolivia, in search of diesel

Bolivia, in search of diesel

Post Info

Date | July 2025 |

Status | Done / Visited |

Last updated | 03 October 2025 |

Page read | 218 |